Art Scene Where Laid on Table and Let Peoiple Do Anything

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a6/d5/a6d5f5e7-b6bf-4d9f-a885-29ed7dc7baaf/chapter_12_05_aip-klaus-copy.jpeg)

Museums usually prohibit visitors from touching artwork—let lonely sanction sticking pins in an artist, cutting off her apparel or gashing her neck with a knife as part of a show.

Merely that's precisely what some audience members did to Marina Abramović during her iconic 1974 work, Rhythm O , which turned out to be a frightening experiment in crowd psychology. Performed in a Naples, Italy, gallery, Abramović placed 72 objects on a table, including pins, needles, a hammer, carving knife, bullet and a gun. She invited viewers to do whatever they desired with any of the items, giving the public six hours of complete physical control over her. As gallery instructions explained, the artist was the object. At one betoken, someone loaded the pistol and placed it in Abramovic's paw, moving it to her clavicle and touching the trigger.

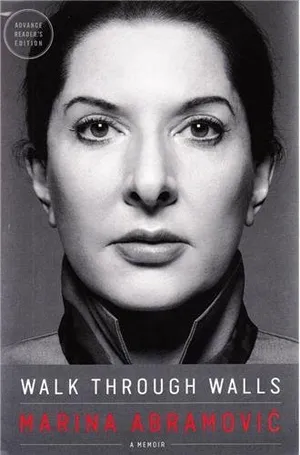

When the show finally ended, according to her upcoming memoir, Walk Through Walls, a battered Abramović staggered to her hotel room, looking "like hell," half-naked and bleeding—"feeling more lone than [she'd] felt for a long fourth dimension." Just, equally she tells readers, Rhythm 0 encapsulates the next four decades of her work: to phase the universal fear nosotros all have of suffering and mortality to "liberate" herself and the audition, using "their energy" to push her body as far as possible.

Walk Through Walls: A Memoir

A remarkable work of performance in its own correct, Walk Through Walls is a vivid and powerful rendering of the unparalleled life of an boggling artist.

Wall Through Walls traces Marina'south life, from her young childhood under Tito's government in post-WWII Yugoslavia to her collaboration with manner house Givenchy for its 2015 runway show in New York, the city she now calls home. Built-in in 1946, Abramović started as a painter at Belgrade's Academy of Fine Arts, just had a deeper interest in more conceptual work. Marina proposed her first solo performance, Come Wash With Me, to the Belgrade Youth Middle in 1969, where she planned to install laundry sinks, inviting visitors to remove their clothes so she could wash, dry, and iron them. The Center rejected the idea, merely she kept at it—her official foray into performance art, a serial of audio installations in the early on 1970s.

While the book covers matters that have been well-trodden, Abramović offers some insider-anecdotes that readers should bask finding (spoiler: decision-making urination is an result when Abramović plans pieces). The memoir'due south most powerful moments come when Abramvoic shares the nigh intimate details of the romantic heartaches she'due south endured. Marina pulls no punches about the men she's loved and the artist feels feels more nowadays than e'er.

Hailed as a pioneer, Marina is often called the grandmother of performance art.. "She has been hugely influential," says Stephan Aquiné chief curator of the Smithsonian's Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. "One of her greatest influences is that she's revealed how time transforms simple gestures into profoundly meaningful and stirring events." It's one thing to practise a certain action for a few minutes, he explains. Merely when Marina sustains or repeats an activity for a long menstruum, her endurance changes the human relationship between the creative person and the viewer into something more visceral and intense.

It's a medium, though, that can feel theatrical and affected, especially for those already skeptical nigh contemporary art to begin with. Inside the fine art world, critic Jerry Saltz has called Abramović's pieces "deadline masochistic." On occasion, Marina herself has blurred the line between her work and other dramatic displays of stamina. In the 2012 documentary, The Artist is Present, her gallerist, Sean Kelly kiboshes a joint-performance idea that David Blaine has proposed to Marina for her MoMA retrospective. Blaine, Kelly explains, is too pedestrian. He traffics in magic— whereas she inhabits the highest echelons of the art world. But Abramovic'southward regard for Blaine— who is often called an endurance artist— raises the question: why practice Abramović's feats of strength get the high fine art imprimatur? After all, Blaine subjects himself to farthermost mental and concrete duress, when say, he'southward "cached alive" in a plexiglass coffin for a week or encased in a block of water ice for 63 hours. Marina laid naked on a cross, made of ice blocks, in one of her performances.

At the very least, Marina's art sits somewhere, equally one Atlantic writer put it, "at the juncture of theater, spirituality and masochism." Some examples from her prolific career: Abramović carved a five-pointed star in her stomach with a razor blade for Thomas Lips. She crawled around a gallery flooring with a large python in Three. She sabbatum naked before an audience and brushed her hair to the point of hurting, yanking out clumps for Fine art Must Exist Beautiful, Artist Must Exist Beautiful.

And of course, in what many consider her greatest accomplishment, she sabbatum on a wooden chair for 700 hours, over the grade of 3 months, silent, staring at visitors, ane-by-i in The Artist Is Present. The show brought over 750,000 visitors to MoMa and moved many viewers literally to tears. There's even a tumblr, Marina Abramović Made Me Cry. A cognitive neuroscientist at New York University, Suzanne Dikker, was then intrigued by the phenomenon, she collaborated with Abramović on a research project called, "Measuring the Magic of Mutual Gaze." Two people, wearing portable EEG headsets, stare at each other for thirty minutes (much like the evidence), then Dikker can measure where their brainwaves synchronize.

In the last decade or and then, Abramović has drifted more mainstream, seen by her critics as a sellout for trying to cash in her notoriety. It's somewhat of a Catch-22. Her recent work lacks the claret and nudity that helped make her an edgier upstart, simply Abramović "the brand" is certainly more pervasive in pop civilisation. Her 2002 functioning, The House with the Bounding main View (my personal favorite from her oeuvre), was meticulously parodied, ten months later, on "Sex activity and the City". Carrie Bradshaw visits a gallery where an creative person is living on a raised platform; the only egress is a fix of knife-runged ladders. Like Marina, the artist isn't talking or eating for xvi days, in an endeavour to change her own "energy field," that of the room and possibly even that of the earth (Marina'due south performance lasted for 12 and her memoir never mentions The House with the Ocean View is near "the world").

Solidifying her ubiquitous status, in 2013, Jay Z adapted The Artist Is Nowadays for his music video, "Picasso Baby." Filmed in a typical white-box Chelsea gallery, the creative person and rapper dance, staring intently at one another. In exchange for her material, Jay Z plain agreed to a make a donation to her institute in Hudson, New York, where she plans to teach the "Abramović method." She describes the method in her Ted Talk as heightening people's consciousness and power to live in the moment—what everyone else calls mindfulness.

Branislav Jakovljevic, a professor of functioning theory at Stanford's department of theater and performance studies sees a stark difference betwixt theater and fine art such every bit Marina's. He explains that theater is representational just Abramović is profoundly presentational. "What you encounter is actually happening," he says. "There are no illusions or questions nigh how she's doing something." Also, Abramović'south audiences participate by submitting themselves to whatsoever might happen, he says, much in the manner that she does. An intense illustration, fifty-fifty for Marina: in Rhythm 5, the artist lay inside a flaming wooden star and lost consciousness every bit the fire consumed the oxygen around her head. Information technology was a viewer who pulled her to safety.

"Masochism involves unconsciously motivated pain and suffering," explains Dr. Robert Glick, professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons and erstwhile manager of the academy's Center for Psychoanalytic Preparation and Research. "Therefore," he says, "non everything that involves suffering is masochism." Yes, Marina Abramović inflicts hurting on herself— but as a grade of deliberate communication and bear upon on her audition. Glick likens Marina Abramović'south activities to people who participate in hunger strikes equally a form of protest. Marina spends months or years planning her performances and he points out, that's speaks to a form of artistic ambition more a masochistic drive.

In fact, there's a poignant scene in her memoir, where her relationship with Ulay ("the godfather of performance art," Marina's professional and life partner of 12 years), is woefully deteriorating. During a fight, Ulay hits her face for the first time— in "existent life"— every bit opposed to during a functioning slice, such as Calorie-free/Night, where the two traded violent slaps for 20 minutes. And for Marina, the life/art boundary had been irrevocably breached.

Her autobiography probably won't change everyone's mind on the power of functioning art. People who find her efforts or the whole genre alienating and contrived will likely feel the same after Walk Through Walls. Merely for those who believe her grueling approach makes her a visionary, the memoir reveals a sensitive, steadfast — at times, surprisingly banal— woman, who can push button her body and mind past all our levels of fear and exhaustion in the name of fine art.

Jacoba Urist is an art and culture author in New York.

Post a Comment for "Art Scene Where Laid on Table and Let Peoiple Do Anything"